In my launch announcement earlier this week, I introduced the Path of Manliness as a response to the growing disconnection and confusion men face in today's world. Now I want to explore a basic pattern I've observed consistently in my decade of working with men.

The statistics tell a sobering story: despite unprecedented levels of material abundance, we see men suffering from rising suicide rates, epidemic levels of pornography addiction, declining marriage rates, and increasing isolation. We were told that getting more of what we want would solve our problems, but the opposite is happening. These are symptoms of a deeper ailment that affects men regardless of their apparent "success" in life.

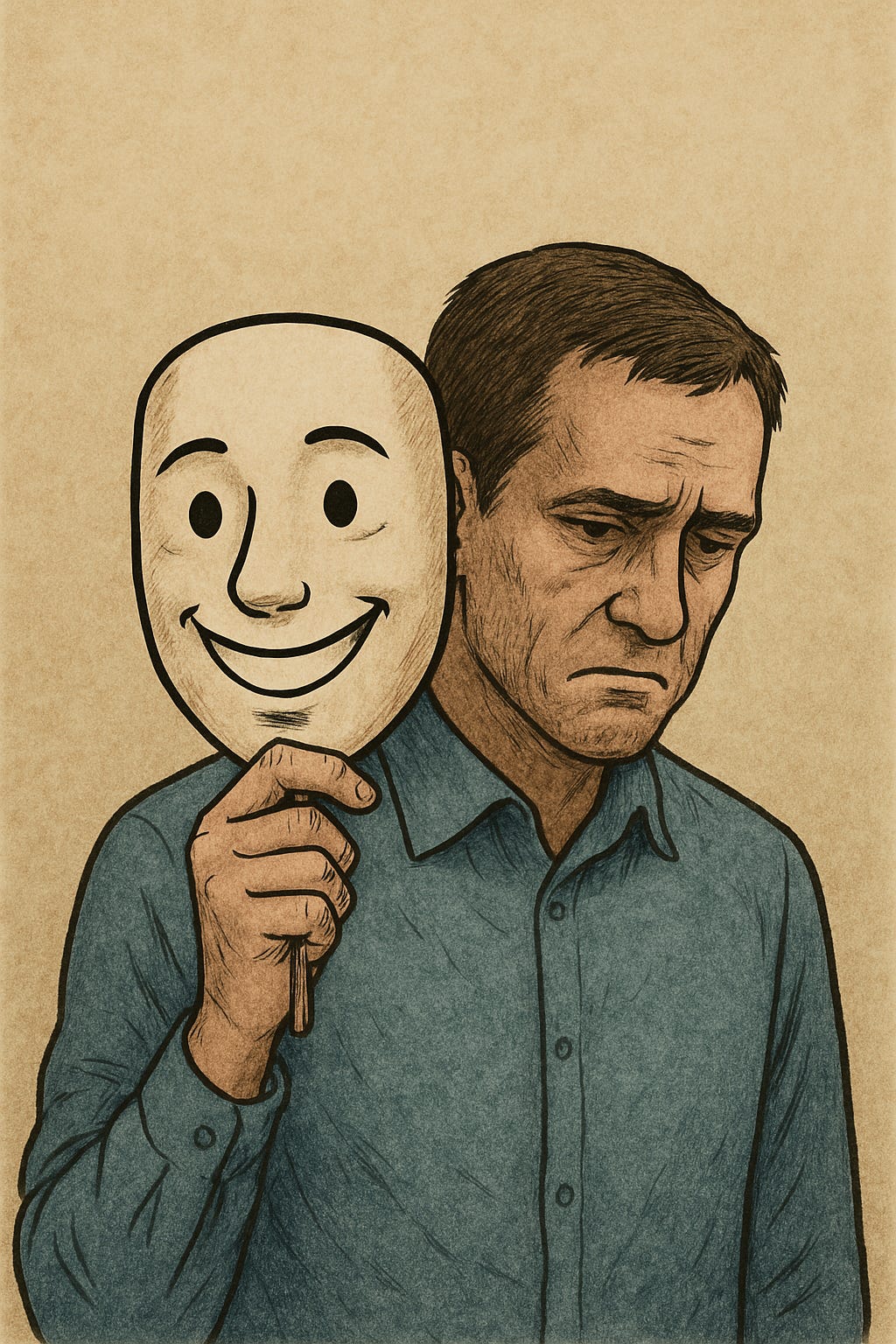

I call it the "man-child syndrome"—men who, disconnected from the wisdom of previous generations, remain stuck in patterns of adolescent thinking and behaviour. These men often appear successful externally but experience a profound internal emptiness that no achievement seems to fill.

Most interestingly, the man-child syndrome manifests in two seemingly opposite forms: the "Nice Guy" and the "Bad Boy." Though appearing different on the surface, these patterns share a common foundation that keeps men trapped in immaturity.

The Nice Guy: The Pleaser with Hidden Agendas

In 2002, Dr. Robert Glover published "No More Mr Nice Guy" (NMMNG), a book that created a paradigm shift in how countless men viewed themselves.

Glover defines a "Nice Guy" as a man who seeks approval and validation by trying to be what he believes others want him to be. This behavior often stems from early life experiences where he internalized the belief that his natural self was unacceptable, leading to a pattern of people-pleasing and self-suppression.

The Glover's Nice Guy is not genuinely nice at all. Behind his mask, he is dishonest, manipulative, and controlling. His false nature manifests as passive-aggressive behaviour or occasional outbursts of uncontrolled rage. Unable to set proper boundaries, he often finds himself isolated and lonely, struggling with addictions and difficulties in intimate relationships.

The book revealed something many men had never considered: their "nice" behaviours weren't virtues but manipulative coping mechanisms designed to avoid rejection and hide authentic needs. For many readers, it was like having a blindfold removed—suddenly seeing how their people-pleasing patterns had locked them into lives of quiet desperation and false connection.

The Nice Guy operates through what Glover calls "covert contracts"—unstated expectations that "If I do what others want, they'll give me what I want without my having to ask for it." He believes his needs will be met if he's "good enough," eliminating any need for direct communication or potential conflict.

The Nice Guy approaches relationships by morphing himself to comply with what others want. He's constantly working for approval, afraid of rejection, and puzzled why his relationships feel so empty despite his tireless efforts to please. He maintains a spotless public image while often harbouring resentment, passive aggression, and sometimes secret behaviours that contradict his "nice" persona.

"Nice Guys" are the most common type of men I meet on my retreats. Take Chris, a 42-year-old husband I worked with. Chris prided himself on being a man who loved and appreciated women—always serving, never expressing needs, being a good friend, and never complaining. Yet beneath the surface, he harbored resentment when others didn't reciprocate his sacrifices or give him what he truly wanted.

"I've been doing everything right," he confessed. "Why doesn't anyone ever think about what I need?"

Glover details how this pattern often originates in childhood. The Nice Guy learned early that his authentic self was somehow unacceptable or dangerous. Often, he witnessed an overly dominant or aggressive father and resolved never to be "that kind of man." Instead, he built an identity based entirely on being the opposite—compliant, non-threatening, and excessively considerate.

The Nice Guy's relationships follow a predictable pattern:

He morphs himself to become what he thinks others want

He hides his authentic needs and desires

He gives to get, though generally not acknowledging this transaction

He grows increasingly resentful when his unspoken needs aren't met

He either explodes in occasional outbursts or retreats into secret behaviours (pornography, emotional affairs, passive-aggressive actions)

What makes the Nice Guy pattern particularly insidious is its appearance of virtue, even to the man himself. Our culture celebrates selflessness and consideration. The Nice Guy unconsciously weaponizes these virtues, using them as a strategy to get his needs met without taking the risk of direct communication. He fears rejection so that he never allows himself to be truly known, even to himself.

The Bad Boy: Honest But Selfish

As Glover's work gained traction, many men recognized their Nice Guy patterns and sought to break free. But what happened next revealed a limitation in Glover's framework.

The subtitle of NMMNG is telling: "A Proven Plan for Getting What You Want in Love, Sex, and Life." The book structure focuses entirely on helping men “get what they want." It's packed with stories of Nice Guys who struggle in every aspect of life, contrasted with men who dropped being nice and thereby achieved what they wanted.

The promised transformation isn't toward maturity but toward effectiveness in getting one's desires met. This leads many men to swing to the opposite pole—what I call the Bad Boy.

The Bad Boy has shed the Nice Guy's manipulative mask. He proudly puts his needs first. He makes his own rules. He's direct about his wants, unapologetic about his behaviour, and refreshingly authentic compared to the Nice Guy's constant people-pleasing. He doesn't fear conflict or rejection—he simply moves on when a situation no longer serves his desires.

Take Marcus, a former "recovering Nice Guy" I worked with. After reading NMMNG, he embraced radical honesty about his desires. He began telling women exactly what he wanted sexually from the first date. He stopped doing things he didn't want to do. He felt liberated from his people-pleasing prison.

Initially, this brought Marcus relief from his anxiety and cognitive dissonance. He experienced more sexual "success," more apparent freedom, and less internal conflict. But six years later, he returned to our group confessing emptiness and disconnection:

"I'm getting everything I thought I wanted, but it feels hollow. Especially with women. It’s almost like I have become too jaded and lost the ability to really love."

Self-Acceptance vs Self-Knowledge

Glover proposes "the integrated man" as the solution to the Nice Guy syndrome. The main thrust is to accept all aspects of oneself, including imperfections. "If you are a frustrated Nice Guy," Glover promises, this book will ensure that you “accept yourself just the way you are."

This approach incorporates psychological concepts like "integrating your shadow" and "healing the inner child" from Jungian therapy. However, without grounding in traditional frameworks—particularly having disregarded Christian principles—Glover provides no solid foundation for how his Integrated Man can find true fulfillment. His message reduces to "accept yourself completely, create your own rules, and take what you want without shame."

In my experience, true healing involves self-knowledge rather than self acceptance. This means accepting the truth of one’s self and also one’s brokenness, not celebrating it. Christianity teaches repentance—not merely integration—as the path to transformation.

While Glover points to ideas of responsibility, purpose, and emotional maturity through his concept of the Integrated Man, his vision lacks grounding. Without an objective standard of good or compelling reason to choose virtue, "integration" becomes self-referential. Glover’s recovered Nice Guys remain trapped in a childish cycle of endless self-focused desires. That is why I call them Bad Boys, man-children who have found further justification and refinement of their selfishness.

The Insatiable Nature of Wanting More

Desire is infinite and unquenchable. Reaching your desires simply generates more desire and sets a higher bar for getting the same satisfaction. Asked, how much money it takes to make a man happy, John D. Rockefeller responded “Just one more dollar.” This is a man who attained a personal fortune of more than 1,5% of the USA’s GDP, and yet concluded that his desire for more money was always going to be a “+1”.

These findings echo what the Church Fathers have always known: that the heart is insatiable until it rests in God.

Glover assumes that the path forward is to be able to get more of what you want and tells us that self-acceptance is the pinnacle of growth. But in a society of material abundance and spiritual poverty, men are increasingly realising that they do not find fulfilment in chasing selfish desires. While Glover insists that a man should make his own rules in life, tradition would guide us to show that fulfilment comes from transcending childish fixation on the things we want for ourself.

Horizontal Swinging vs. Vertical Growth

Here's the crucial insight that transformed my understanding: Nice Guys and Bad Boys aren't separate personality types—they're just poles on the same horizontal axis of immaturity.

Man-children swing between these extremes throughout their lives. When Nice Guy strategies fail to get them what they want, they try Bad Boy approaches. When Bad Boy approaches leave them lonely, they return to Nice Guy patterns. But this horizontal pendulum never leads to maturity.

I spoke with Dr. Mike Frazier of Strong Men, Strong Marriage, who describes what he calls the "mosquito cycle" in marriage. Men focused on their own desires perform acts of service to get something in return—typically sex—from their wives. This might work temporarily, but when the wife realizes these acts come with strings attached, she withdraws.

The man then becomes upset, perhaps more assertive, and may seek other ways to fulfill his desires. While these new approaches might work briefly, eventually he missteps. Feeling guilty, he returns to the beginning of the cycle—now with diminished trust and enthusiasm.

The core issue is that he remains trapped in a self-centered approach to his wife and the world, like a mosquito interested only in drawing blood. Such neediness will never be attractive to a woman.

Vertical Growth Through Tradition

The real solution is not found in more effective strategies for getting what you want. It's found in vertical growth toward maturity where you realize the importance of others' needs. The keys to outgrowing this childishness, which I am working to describe here on The Path of Manliness, lie in wisdom passed down through generations.

This means recognizing the false view of reality assumed by the self-centered paradigm of the man-child. A small child believes he is the center of the universe, acting only to achieve his selfish desires. These desires are typically short-sighted impulses for instant gratification and avoidance of discomfort. The man-child may have more sophisticated strategies and better ways of hiding his intentions, but the driving force behind his actions remains the same as the little boy's—a focus solely on his own needs.

That is why this platform is focused on exploring how traditional wisdom can help us see reality clearly and find our natural role in society. A man who achieves this understands his place as a vital, contributing part of the whole. And he knows that this transformation is worthwhile.

The Prodigal Sons

The Parable of the Prodigal Son1 serves as the perfect illustration. This ancient story, simple yet profound, powerfully depicts the Nice Guy and Bad Boy patterns in their archetypal forms.

The younger brother exemplifies the Bad Boy—selfishly and unashamedly taking what he wants. The older brother perfectly represents the Nice Guy—working hard for his father while harboring resentment, never fully embracing his sonship.

Thus, these insights aren't some new, ground-breaking revelation. In fact, this brief parable provides wisdom about these patterns which has served as a powerful guide for millennia and will likely also outlast today’s psychological theroies.

This is just one example of the trouble we get into when we abandon tradition in the mistaken belief that it was all "myths and fairy tales" not applicable to our modern world. A society that no longer appreciates tradition as a source of wisdom loses its ability to see the treasures contained within it.

Every one of us recognises and is inspired by the qualities of a traditional hero when we see a character in a story who gives up their personal wants, even their own life, for the good of others. And yet, for some reason, we fail to implement this in our own lives, and become petty about the smallest little compromises in what we want for ourself.

Tradition can thus help a man to be rational, seeing reality clearly, incorporating the strengths of both approaches while transcending their limitations. Like the Bad Boy, a mature man is honest about his needs and boundaries—but like the better aspects of the Nice Guy, he considers the impact of his actions on others. He's neither a manipulative pleaser nor a self-centred taker.

Most importantly, the mature man has shifted from self-centred desire to purpose-driven creation. He's no longer primarily concerned with getting his needs met but with building something of lasting value. This vertical dimension through the wisdom of tradition is what's missing in our cultural conversation about masculinity.

The Path Forward: A Brief Preview

In the coming weeks, I'll be exploring a traditional framework for masculine development that offers an alternative to the man-child syndrome. This path focuses on mastering four fundamental roles that have guided men for generations:

The Son – Learning humility, respect, and your place in the generational chain

The Brother – Building authentic male friendships as vital support in all aspects of life

The Husband – Learning to love and lead through service

The Father – Providing, protecting, and passing on wisdom to the next generation

Alongside these roles, I am looking at how men develop the practical skills that forge them into competent and confident men who are respected as an asset to their community.

This summer on the 31st July to 3rd August, we will hold a Path of Manliness Man Skills Summer Gathering here on my homestead where we will dig into the actual work of developing these skills and community.

Join Us on the Journey

If you sense there's something more meaningful available than what modern culture offers...

If you are interested in tradition, manliness, and the path to move beyond Nice Guy and Bad Boy patterns...

Then I invite you to continue this exploration with me. Please subscribe!

Our summer gathering will provide hands-on experience in classical man skills within a community of like-minded men. Read more and sign up here:

In the meantime, consider joining an online Core group. Maniphesto Core is my main “day job”, where I manage a network of groups where men support each other in daily life.

Hey Paul. Very much on point and with great clarity discovered and explained! This is exactly my experience and I have gladly left the swinging path between nice guy and bad boy.

This has opened my eyes. I have a long response, but I don't want to turn this into my forum.